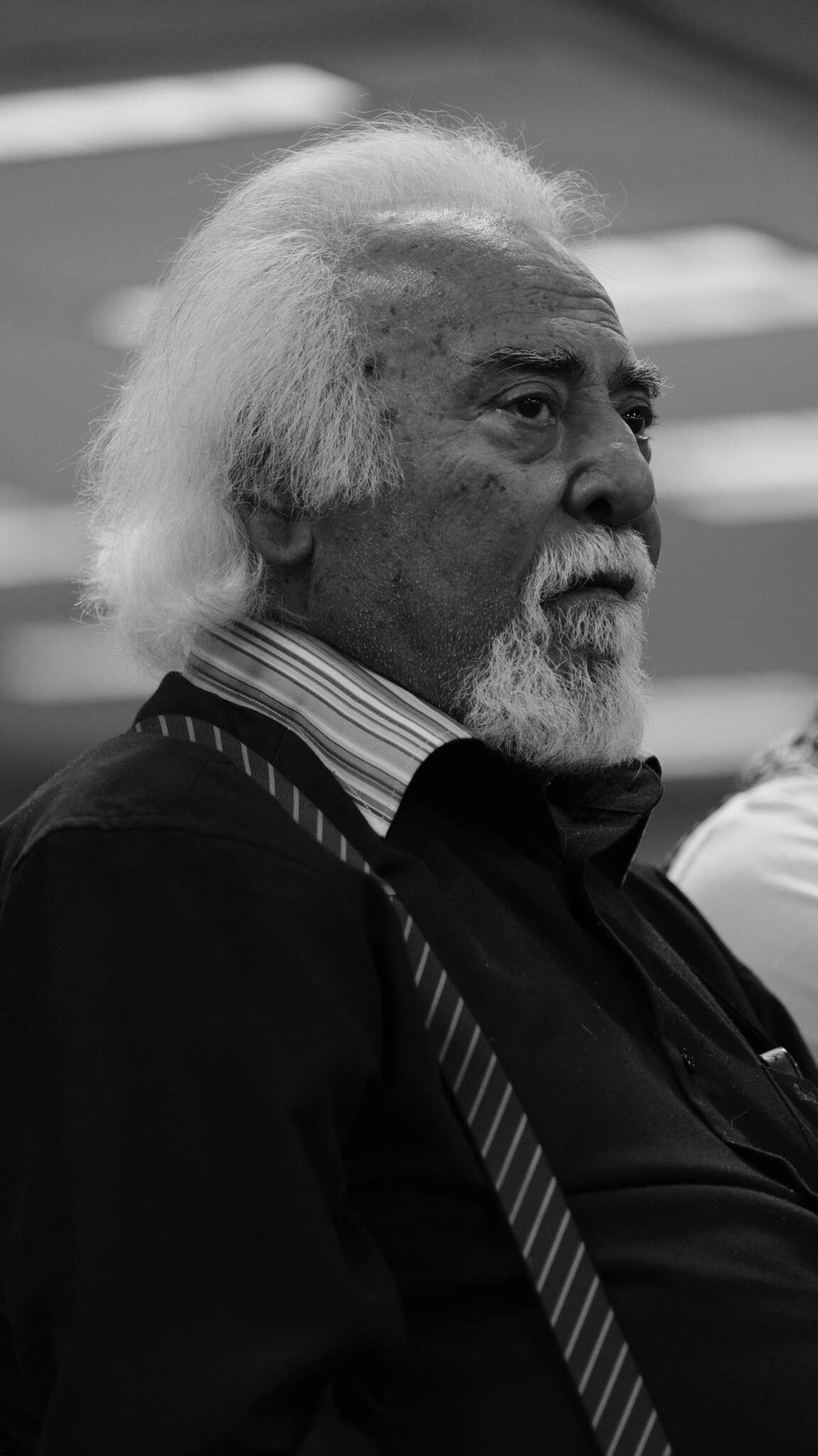

You’ve heard him in Gheysar, Dash Akol, Reza Motori

The music hits before the story does. It curls around your ear like a whisper before the first punch is thrown, the first tear falls, the first cigarette lights. In an interview, he tells the story of where it all began. He was ten, buying single film frames with Masoud Kimiyayi and projecting them in dark rooms like little magicians.

“It was mesmerizing,” he said, “how a dark screen could suddenly light up — and all that magic would happen on it.”

But maybe the seed was planted even earlier — behind a closed door. His father’s Friday night gatherings, men playing instruments, drinking, laughing. The door always shut. But the sound trickled through — the rhythms, the energy, the forbiddenness of it all — until the next morning, when the room emptied and little Esfandiar would sneak in and try to coax those same sounds from the instruments left behind.

The tombak, the accordion, the santur—they became his playground. By the late 1950s, he was already performing under a pseudonym on the Air Force radio station (the main national station wouldn’t allow musicians to work elsewhere). A quiet rebellion, the first of many.

In his teens, he hung around film studios with Kimiyayi and Faramarz Gharibian. One wanted to act, one to direct — and Monfaredzadeh? He just wanted to make music for movies, even though at the time, Iranian cinema barely acknowledged the role of original scores. That didn’t matter. He kept showing up.

Later, he studied music formally, dropped out when it didn’t align with what he wanted to make, recorded with artists like Googoosh, Farhad, Sussan — arranged pieces that threaded politics, poetry, and heartbreak all in one breath.

And even when exile arrived—when he had to leave Iran because his music and mind were too loud for what was allowed—he didn’t stop. In the U.S., he co-founded a traditional Iranian music ensemble, Oshagh, to keep classical music alive across borders. He composed scores for political films, set poetry by Rumi and Forough and Fereydoon Moshiri to music, collaborated with voices like Dariush and Zoya Sabet. His scores wandered into exilic cinema, theater, underground movements, cassette tapes passed hand to hand.

He didn’t just write music. He remembered with it. Protested with it. Survived with it. And when the light hit the screen — whether in a Tehran movie house or a community center in L.A. — you could always hear that ten-year-old boy, eyes wide, watching the dark come alive.

Photography Sina Rabiei